How One University Discourages and Dismisses Students’ Reports of Sexual Assaults

The school founded by evangelist Jerry Falwell ignored reports of rape and threatened to punish accusers for breaking its moral code, say former students. An official who says he was fired for raising concerns calls it a “conspiracy of silence.”

Note: This story includes descriptions of sexual violence and attempted suicide.

by Hannah Dreyfus, photography by Sarah Blesener for ProPublica

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

When Elizabeth Axley first told Liberty University officials she had been raped, she was confident they’d do the right thing. After all, the evangelical Christian school invoked scripture to encourage students to report abuse.

“Speak up for those who can’t speak for themselves, for the rights of all who need an advocate. —Proverbs 31:8.” It was quoted in large type across an information sheet from the school’s office tasked with handling discrimination and abuse.

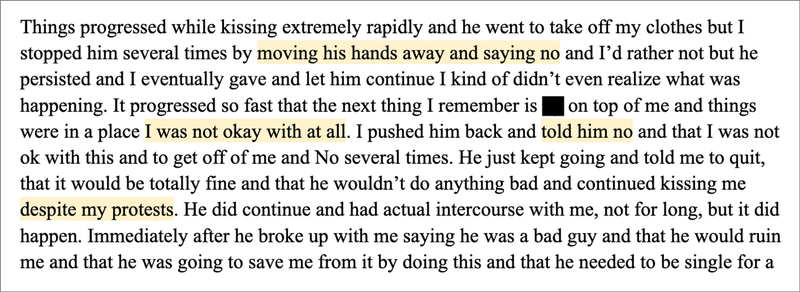

Axley was a first-year student at Liberty in the fall of 2017. She had been at the school less than three months. One Saturday night, she went to a Halloween party at an off-campus apartment and drank eight shots of vodka, along with a couple of mixed drinks. She doesn’t remember much after that, until, she recalls, waking up with a fellow student on top of her and his hand pressed over her mouth. (The student denies Axley’s allegations.)

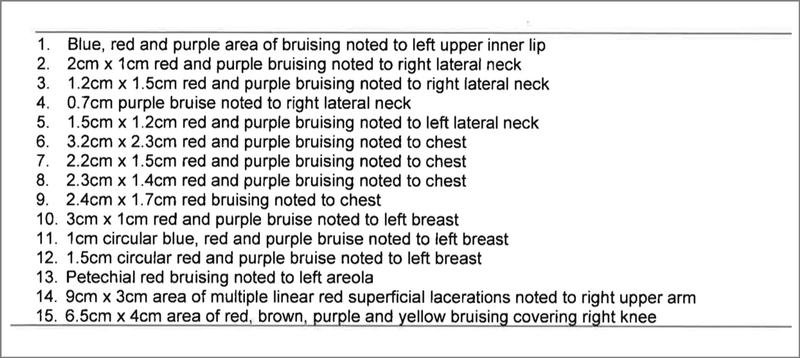

After Axley returned to her dorm, she called the campus police department. One of the officers drove her to the local hospital, where, records show, a nurse documented 15 bruises, welts and lacerations on her arm, face and torso.

Axley wasn’t sure what to do next, but she did know that she wanted the man to “stay away from her,” as she recalled. So when Axley got back to her dorm that Sunday morning, she again told someone at Liberty, her resident adviser.

The RA, Axley said, told her not to report it, saying Axley could be found to have violated the school’s prohibition against drinking and fraternizing with the opposite sex.

Instead, the RA offered to pray with Axley.

“I was really confused,” recalled Axley. “They were making it seem like I had done something wrong.”

Axley didn’t want to pray. She wanted the school to do something about what had happened. “I didn’t want to get fined or punished, but I wasn’t going to let this keep me from reporting my assault.”

The next day, Axley went to the school’s federally mandated office for investigating sexual harassment and violence.

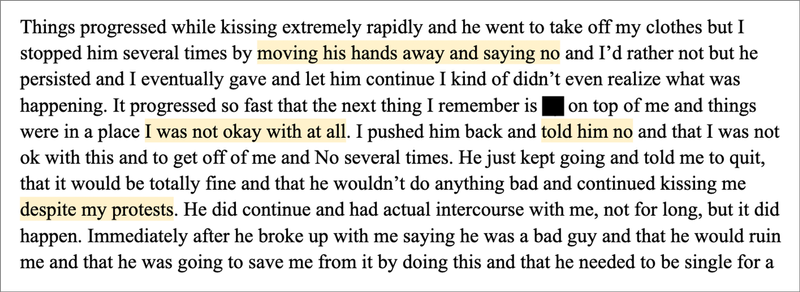

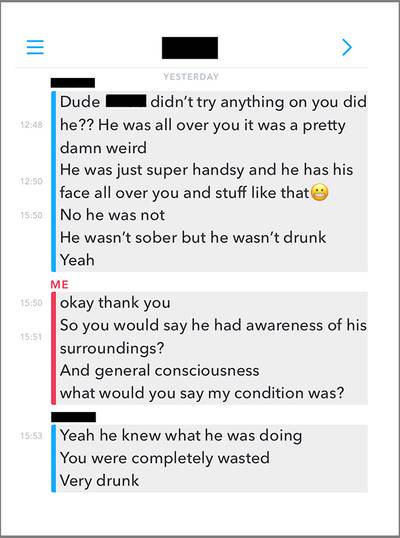

She had prepared. Axley saved texts from that weekend. “He was all over you,” one concerned friend had written to her. It was “pretty damn weird.”

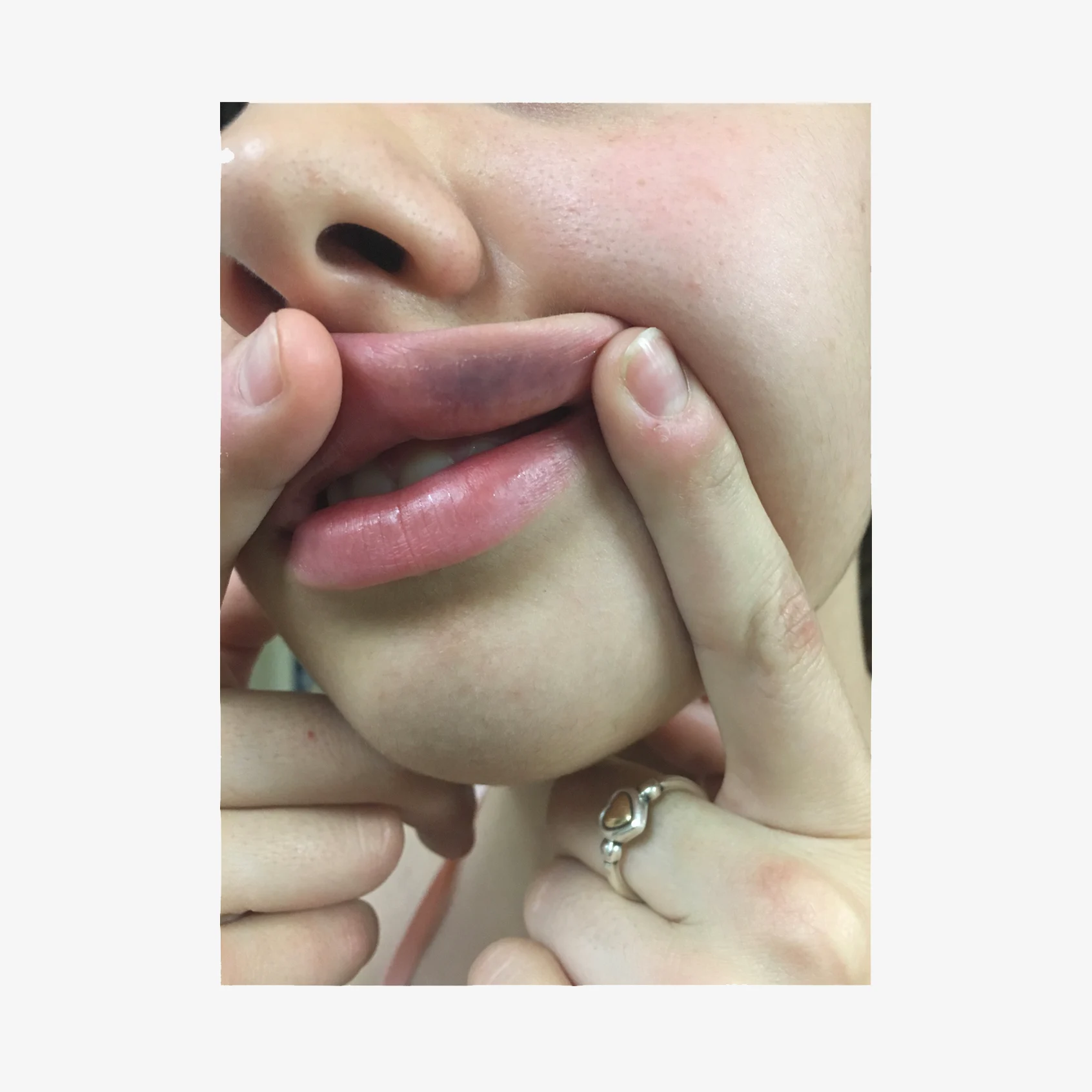

“I fucking remember making noise and him covering my mouth oh my god,” Axley texted another friend in the early morning hours. She also took photos of the welts across her chest, multiple lacerations on her right upper arm and a bruised lip.

“When I went into that office,” Axley said, “I was ready.”

But Elysa Bucci, the official who took the complaint, didn’t seem interested, Axley recalled. Bucci was a lead investigator with Liberty University’s equity office, which is responsible for looking into potential violations of Title IX, the civil rights law that bans sexual discrimination on campuses that receive federal funding. Liberty students receive almost $800 million a year in federal aid.

Instead of considering her evidence, Axley said, Bucci started throwing questions at her: Why had Axley gone to the party? What had she had to drink? How much? “I immediately felt judged,” remembered Axley. (Bucci, who is now a Title IX investigator at Baylor University, declined to comment.)

Then Axley waited. She received email updates saying the school was still looking into her case. After five months, Axley heard from Bucci that Liberty had completed its investigation and a committee was now going to consider the case. Bucci invited Axley to first come to the office and review the file.

Axley went in and looked through the materials. The photos with her injuries, she recalled, were no longer there. Axley said that when she asked what had happened, Bucci told her the photos had been removed because they were too “explicit.”

“I felt like I’d been punched in the stomach,” Axley recalled. “I had been relying on them all these months to take my evidence into account when considering my case, and it wasn’t even in my file.”

Evidence Removed – Liberty removed the following images from Axley’s file.

A few days later, Axley received another email from the university. It said that as the case was moving ahead for a final decision, Axley needed to sign a document acknowledging that she could be found to have violated the university’s code of conduct. The Liberty Way covers nearly all aspects of a student’s life and includes bans on drinking and “being in any state of undress with a member of the opposite sex.”

As the document that Axley received phrased it, by moving ahead with the case, Axley was acknowledging that she herself could face “possible disciplinary actions.”

Universities across the country have long faced scrutiny for their handling, and mishandling, of sexual assault cases. But Liberty University’s responses to such cases stand out. Interviews with more than 50 former Liberty students and staffers, as well as records from more than a dozen cases, show how an ethos of sexual purity, as embodied by the Liberty Way, has led to school officials discouraging, dismissing and even blaming female students who have tried to come forward with claims of sexual assault.

Three students, including Axley, recalled being made to sign forms acknowledging possible violations of the Liberty Way after they sought to file complaints about sexual assaults. Others say they were also warned against reporting what had happened to them. Students say that even Liberty University police officers discouraged victims from pursuing charges after reporting assaults.

Some students still confided in school staff — who at times did not report the cases to the Title IX office, despite being legally required to do so. When students filed complaints themselves, they were often not given legally required notice that they had the option of going to the police.

In the fall of 2013, Diane Stargel sought the help of the university’s mental health counselors, telling the counselor she met with that she’d been raped by another student at a party off-campus. Stargel recalled that the counselor listened and then asked her to sign a “victim notice” that warned she could be found to have broken the Liberty Way if she chose to move forward. Terrified of losing her scholarship, Stargel signed the paper and did not formally report being assaulted.

“I feel like Liberty bullied me into silence after what happened to me,” said Stargel. “I’ve always regretted that I never got my day in court. But at least now I can stand up and say, ‘Yeah, that happened to me.’”

Amanda Stevens also remembers being warned she could be fined for having violated the Liberty Way. After she reported being raped to the school’s Title IX office in April 2015, Stevens recalled that a school official listed her potential infractions: drinking (though she had not been drinking at the time of the assault), having premarital sex and being alone with a man on campus.

“I remember thinking, ‘What? Are you kidding me?’” said Stevens. “‘I could get in trouble for coming forward and reporting?’” After an investigation, Stevens recalled receiving a letter saying the student she had reported for assault had been found “not responsible.”

Liberty officials did not respond to detailed questions sent weeks ago. But one person who received them did ultimately reply: Scott Lamb, who was Liberty University’s senior vice president of communications until earlier this month. Lamb worked at Liberty until Oct. 6, when, he said, he was fired for internally blowing the whistle on the university’s repeated failures to respond to concerns about sexual assault.

“The emails from ProPublica were definitely ignored,” said Lamb. He recalled himself and one colleague trying to make a case for the school to respond. “We said, ‘Listen, the optics of this are killing us. Is there anything we can message — something? A message about empathy? Or that we’re at least working to get to the bottom of this?’ And then it dawned on us: They’re not working to get to the bottom of this.”

Lamb was the point person who had fielded questions from journalists since he took up his post at Liberty in January 2018. He was one of the people to whom I sent a detailed request for comment this month.

Liberty’s lack of response was typical, Lamb explained. “Concerns about sexual assault would go up the chain and then die,” he said. It was “a conspiracy of silence.”

Lamb is filing a federal lawsuit alleging he was fired for raising concerns about Liberty’s conduct. Liberty did not respond to detailed questions about Lamb’s claims.

In the end, Stevens, Stargel and Axley were not fined. But two former students did recall being punished after they reported being sexually assaulted. One said that after she reported being raped to school authorities, she was fined $500 for drinking alcohol and told she had to attend counseling. The former student, who declined to be named, said she was told her transcript would not be released until she paid.

Another student recalled being punished after reporting the potential sexual assault of someone else: Axley.

Logan Pratt, the friend who had texted Axley saying he was concerned by what he saw, told the Title IX office he’d seen Axley being mistreated at the party. He said the university misrepresented what he told investigators, giving the false impression that his testimony undercut Axley’s recollections rather than buttressing them. Then, a few months after the incident, Pratt said Liberty kicked him out of school for drinking and other Liberty Way infractions. One other student also said Liberty misrepresented what she described seeing in Axley’s case.

Ten more former students told me they chose not to report their rapes to campus officials amid fear of being punished. “I knew I would face the blame for putting myself in that situation,” said Chelsea Andrews, a Liberty alum who said she was assaulted by a Liberty graduate student.

A lawsuit filed in July against Liberty recounted similar patterns. The suit, brought by a dozen unnamed former students, asserts that the school failed to help victims of sexual assault and that the school’s student honor code made assault more likely by making it “difficult or impossible” for students to report sexual violence. The suit also claims that the “public and repeated retaliation against women who did report their victimization” created a dangerous campus environment. (Liberty has declined to comment on the pending litigation.)

“Historically, and based on the cases you presented to me, I do not believe Liberty has a conception of sexual assault that is consistent with criminal law, and certainly not with federal civil rights and campus safety,” said S. Daniel Carter, who helped write a law governing how universities that receive federal funding handle sexual assault cases.

Liberty’s handling of cases has often added to the pain of the women I spoke with. As Axley waited for Liberty to decide on her case, she began missing classes. She didn’t want to risk bumping into her alleged assailant. Her grades plummeted. She skipped meals and started sleeping during the day.

“She would have panic attacks constantly — like full body shaking, laying on the floor, no matter where we were, in class or in the library,” said Shannon Gage, a friend of Axley’s and a fellow Liberty student.

Axley’s memories of that time are scattered. She was knocked even further off-balance when the student who she says attacked her filed a lawsuit alleging that Axley had defamed him by recounting her story to others. The sides reached a nonmonetary settlement a few months later. The parties agreed not to disparage each other over “doubtful and disputed claims.” Asked about Axley’s accusations, the former student told me that “I didn’t rape her” and that he also thought that Liberty didn’t investigate the case properly.

Axley has no doubts about what happened. In the months afterward, she scrolled again and again through the photos she had taken of her injuries. They gave her a small measure of calm.

“I would remind myself that I had evidence, and that I had done everything I could to document and report what happened,” she said. “I told myself, ‘How could the school not take action?’ All someone had to do was look at the photos.”

Founded in 1971 by the Baptist televangelist and conservative activist Jerry Falwell Sr., Liberty University remains one of the largest private evangelical institutions in the world. It has a large online operation as well as 15,000 students enrolled at its central campus east of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Liberty has faced sex and financial scandals in recent years involving former university president Jerry Falwell Jr. and his wife, Becki Falwell. But the school continues to appeal to many families and students drawn to Liberty’s strict moral code.

“The goal of The Liberty Way (Student Honor Code) is to encourage and instruct our students how to love God through a life of service to others,” the code says. “The way we treat each other in our community is a direct reflection of our love of God.”

Central to the Liberty Way is a focus on abstinence prior to marriage, what’s known in evangelical communities as purity culture. As the Liberty Way puts it, “Sexual relations outside of a biblically-ordained marriage between a natural-born man and a natural-born woman are not permissible at Liberty University.”

Breaking that ban and engaging in any “inappropriate personal contact,” is punishable by a $300 fine, 30 hours of community service, or possible expulsion.

Mark Tinsley saw how that can play out. Tinsley, who was first a police officer at Liberty University and later an associate dean until he left in 2017, said the school had a tendency to dissuade students from reporting sexual assaults to law enforcement.

Tinsley, who is now a pastor, said he still remembers one case from 20 years ago. Tinsley was first told to check out an alleged rape on the northern end of the campus, but then was instructed to back off because the administration had gotten involved. “I got word that there had been an assault, but that the dean of women had convinced the girl not to press charges,” Tinsley recalled. (The dean in question died in 2015.)

“That was par for the course at Liberty,” Tinsley said.

Erin McAvoy, who worked at a local nonprofit assisting individuals who’d survived sexual assaults, said she often aided Liberty students who were afraid of reporting assaults to the school. “Most of the Liberty students I met with had a friend or a friend of a friend who had ended up in a worse situation after reporting,” she said.

McAvoy said she was also surprised that Liberty students who sought her help frequently did not have information about “their basic options for reporting to law enforcement or even seeking medical help.”

“By and large, the students I worked with from Liberty had been given little to no information about their options,” she recalled.

Former Liberty student Adrianna Rice first contacted the school’s Title IX office in October 2016 to report she’d been raped by a fellow student.

Rice said it happened when the two drove off campus together to hike a local nature trail. Within hours, Rice called her mom. “I don’t think I’m OK,” she told her mom. “I had sex with a guy and I didn’t want to.”

“I asked her, ‘Did you want that?’And she started sobbing and said, ‘No,’” her mother, Kristine Rice, recalled. “And I said, ‘Honey, that sounds like rape.’”

Kristine Rice traveled to Liberty’s campus about a week after the phone call to accompany her daughter to the campus counseling office. Adrianna Rice recalled writing on her intake form that it was an “emergency” and that she had been experiencing “suicidal ideation.” But both she and her mother recalled the counseling center turning her away because they didn’t have any appointments available.

“They referred me to other Christian counselors in the area,” Adrianna Rice recalled.

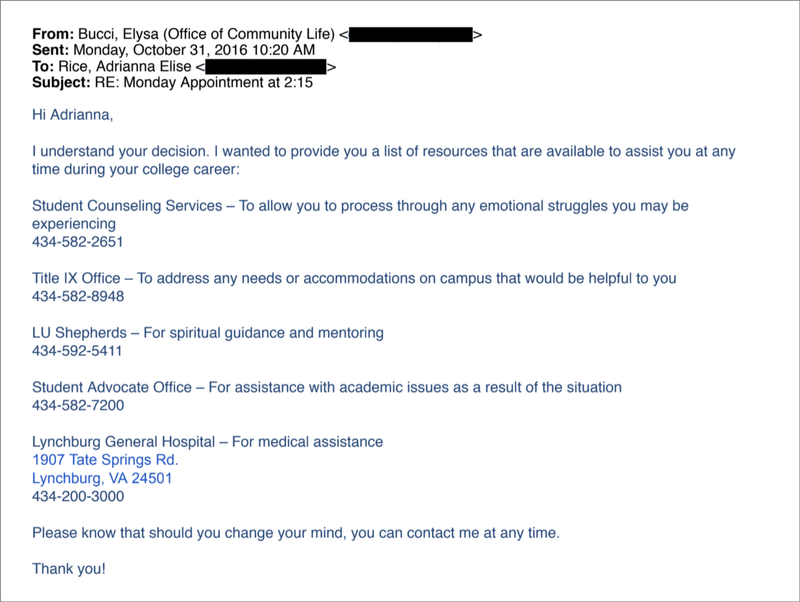

Liberty’s counseling center also referred Rice to the campus Title IX office, which she contacted. Elysa Bucci, who then worked at the office, emailed Rice a list of resources. The list included the campus spiritual guidance center, a local hospital and the student counseling center.

Law enforcement was not on the list, despite a federal law requiring that students reporting sexual violence be told about that option.

“I was never informed that filing a police report was even an option,” said Rice. Figuring Title IX was her only path to justice, Rice decided to open a formal investigation. During the investigation and appeals process, Rice recalled, Bucci repeatedly told her not to speak to anyone else about the case — including law enforcement — because it could compromise the Title IX investigation.

“I felt like a gag order had been placed on me after I had already experienced a trauma,” said Rice, who described avoiding the subject of her assault even with friends and family while the Title IX investigation was underway.

Amanda Stevens, one of the women who was told to sign a form acknowledging her potential violation of the Liberty Way, said she also was not informed of the option to file a rape report with law enforcement after she reported to the Title IX office in April 2015. “They didn’t mention anything like this to me at all,” she said.

And when Diane Stargel met with a Liberty University mental health counselor and told her she’d been sexually assaulted, the counselor not only had Stargel sign a victim notice about her own potential violation of the Liberty Way, but, Stargel recalled, also told her to initial language in the document promising she wouldn’t report the case to police.

Experts said the pattern appears to be a violation of the Clery Act, which requires schools to inform students reporting sexual assaults about the option to go to law enforcement and to assist in that reporting if necessary.

“Hearing that a university official was unlawfully and improperly advising a survivor about her rights and options strikes at the core of my ire,” said Laura Dunn, a lawyer and expert on campus sexual assault who reviewed the facts of Rice’s case.

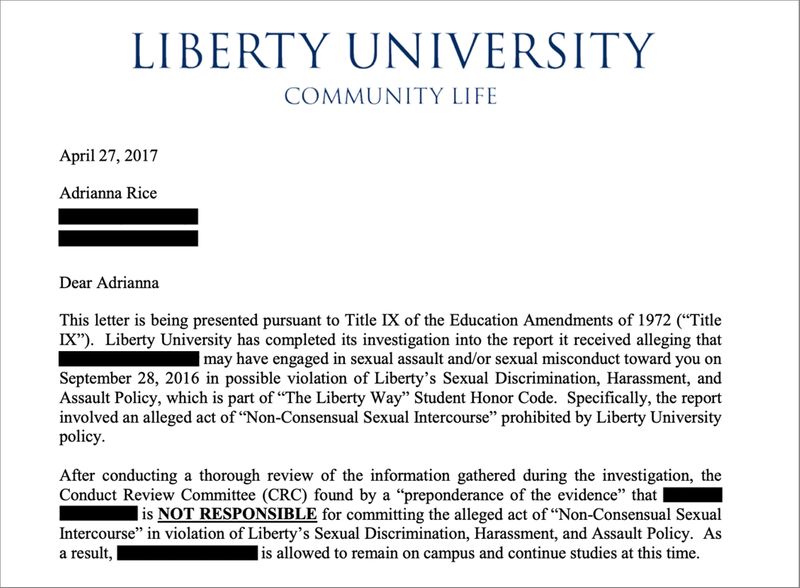

Other aspects of Liberty’s handling of Rice’s case also stuck out. Rice said she had given the school a copy of a text her alleged assailant had sent admitting what he did. Liberty’s letter summarizing its decision on the case did not cite it. The letter concluded that the man was not responsible.

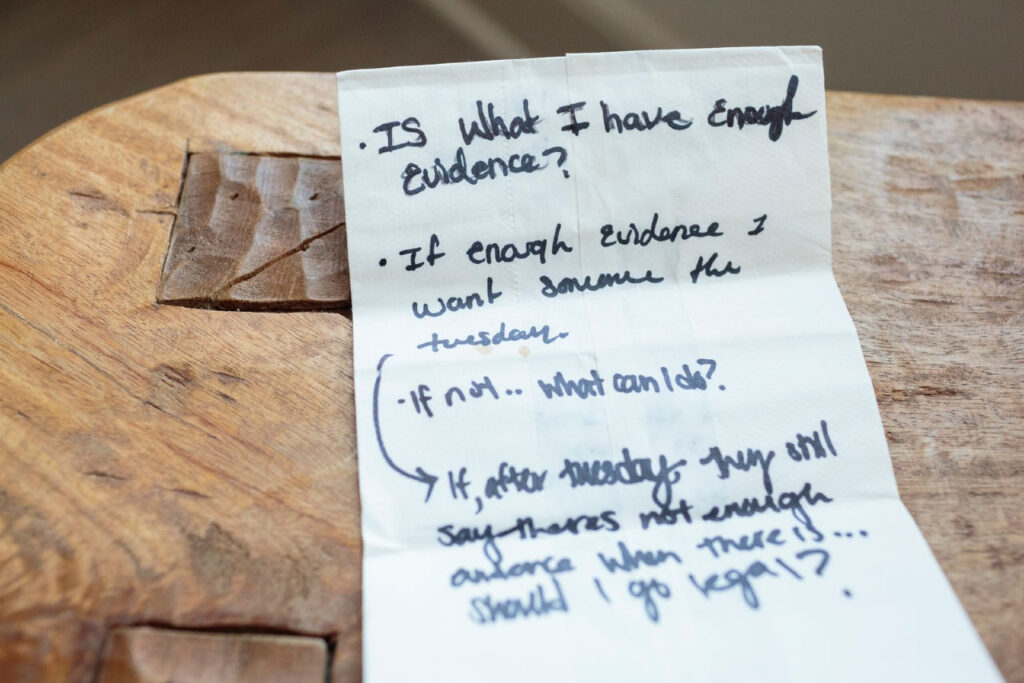

Rice appealed the decision and attended a hearing about it along with McAvoy, the advocate. They were stunned by the appeal committee’s repeated questions about “how and why I had put myself in a situation where this could have happened,” remembered Rice. In her handwritten notes from the day, Rice jotted down questions she wanted to ask the committee members: “What definition of rape are you going off of?” and “What is counted as valid evidence?”

Shortly after the appeal hearing, Rice was informed that the committee had decided to uphold the Title IX office’s original decision by a “preponderance of the evidence.”

Rice then turned to university police for help. Rice provided me with a copy of the intake form she had filled out. But Rice said that when she spoke to Liberty’s campus police chief, Col. Richard Hinkley, he discouraged her from taking the case further.

“He told me all the details I had written down in my personal statement could be turned against me, and that a jury would likely kill my case,” she said. “He essentially discouraged me from continuing.”

Hinkley and the department did not respond to requests for comment.

Title IX requires university officials to report any accusations of sexual violence to a designated Title IX coordinator. That didn’t happen after Liberty student Mary Kate McElroy told her track coaches that she had been pressured by other students to have sex during her first year at the school. McElroy said the men were several years older and much larger than she was. She said she eventually said yes out of fear of “what they might do or say if I said no,” and because she was afraid of being penalized for breaking the Liberty Way.

“I had already let a guy drive me to his apartment, and I knew I wasn’t supposed to be there in the first place,” McElroy said. “I felt like I had no way out.”

“I turned to them for help,” said McElroy about telling her coaches in the spring of 2018. “I didn’t yet understand that what had happened to me was assault, but I knew something was wrong.”

Rebekah Ricksecker, one of the two coaches McElroy spoke to about the incidents, said she regrets not “pushing Mary Kate further” for details about what had happened.

“Had I thought it was assault, I would have filed a report,” Ricksecker said. “At the time I assumed that her discomfort and embarrassment came from breaking the Liberty Way — now I think maybe there was more to it.”

The second coach did not return requests for comment.

Around the same time, McElroy told her resident adviser both about being coerced into sex and her coaches’ lack of follow-up. “I remember Mary Kate telling me she had talked to her coaches about what had happened, and they hadn’t reported it up the chain,” said the RA, Liz Howe. “That broke my heart.”

Howe reported McElroy’s case to the school’s Title IX office, which got in touch with McElroy and encouraged her to file a formal complaint. But by then McElroy had already decided to drop out of Liberty and was planning to leave campus in a few days.

She declined to pursue her case further. “I didn’t have it in me,” McElroy explained. “I was leaving Liberty, and I thought I could leave what happened to me behind.”

Like many universities, Liberty has an amnesty policy to protect students who self-report dangerous or illegal activities, such as underage drinking, in the course of reporting sexual violence or other abuse. In Liberty’s case, the policy has been expanded in recent years to protect students who self-report violations of the Liberty Way, including premarital sex.

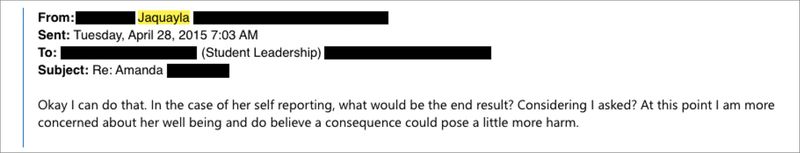

Internal email shows how the policy can work. When Amanda Stevens told her RA that she had been raped, the adviser immediately emailed her boss and recounted what Stevens had told her.

“I then asked her if she had sex with him and she said that she had,” the RA, a graduate student named JaQuayla Hodge, wrote to her resident director, a full-time Liberty staffer. “However, she mentioned that the first time he basically forced himself on her. She would tell him over and over to stop and he wouldn’t.”

The question of whether Stevens could be penalized for potential violations of the Liberty Way immediately came up. Hodge wrote that she was worried about it.

“In the case of her self-reporting, what would be the end result?” Hodge asked her boss in a follow-up email. “At this point I am more concerned about her well-being and do believe a consequence could pose a little more harm.”

Bethany Holt, the school official who ended up handling Stevens’ case, responded that Stevens’ disclosure would be treated as a “self-report,” indicating that she would not be penalized for breaking the Liberty Way.

“At this point, it sounds like anything she confessed to that was a violation of the LU Way would be considered as a self report because we had no prior knowledge of these activities,” Holt wrote. “The allegations of assault we do want to take seriously and would take precedence over the other possible violations.”

Still, Stevens recalled, it was Holt who instructed her to sign a form acknowledging that she may have broken the Liberty Way and warned her she could face fines. Holt, who remains on staff at Liberty, did not respond to requests for comment.

Hodge, who served as an RA between 2012 and 2015 and then as a supervising resident director until 2017, described being troubled by what she saw as a pattern of the school not properly handling cases she brought to them. As a resident director, Hodge began following up with the complainants she referred to the Title IX office because, she said, she “didn’t trust my girls were fully getting what they needed.”

Hodge was shocked to learn that Stevens had been required to sign a form acknowledging that she had potentially violated the Liberty Way.

“If I had heard that, I would have said something,” said Hodge. “I made it clear that it would not be fair for her to be punished if she came forward.”

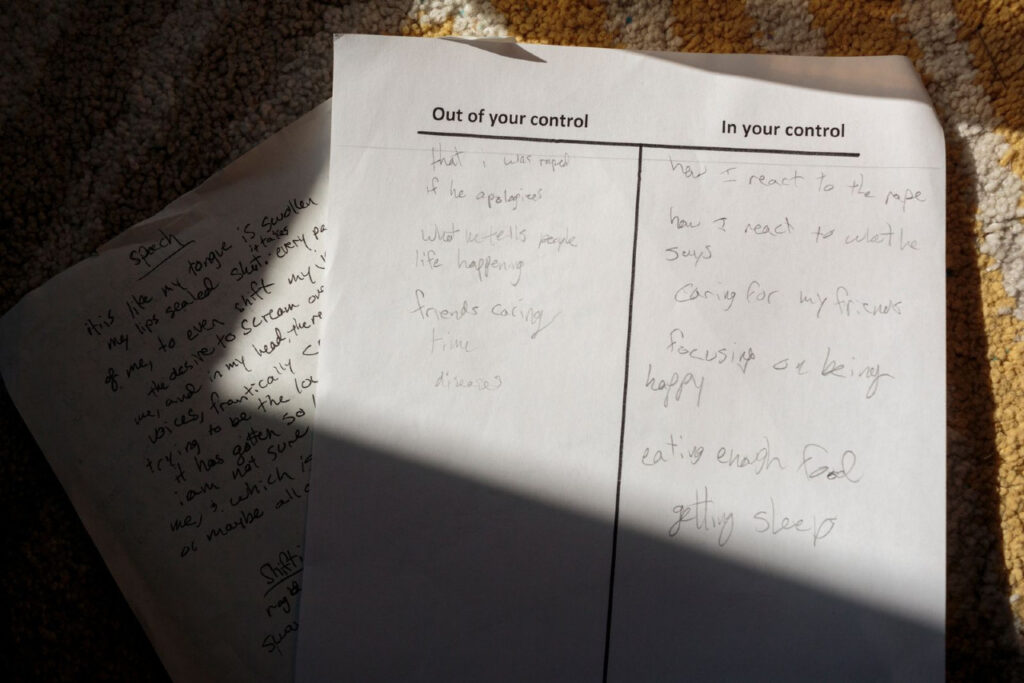

Six weeks after Elizabeth Axley told Liberty University officials she had been raped, she sat on the floor of her college dorm room with her laptop and typed out a brief note:

“He did this to me/Crushed my spirit/stole those I care about/stole something from me. … I can no longer go on like this.”

Two days later, she woke up in the hospital. She stayed for a few days, then went back to campus to resume her freshman year. (If you are considering hurting yourself, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or go to speakingofsuicide.com.)

“I tried to keep functioning but I felt so disconnected from everything going on around me,” Axley recalled. Sometimes, she would forget what she was doing midaction. Sometimes she would just stare straight ahead, unresponsive to the cues around her. She felt “so far away” from her fellow students, who continued going to class and attending social events as though nothing had changed.

In her email correspondence with the Title IX office during this time, Axley requested several notes to excuse her repeated absences from classes.

It was in March that Axley got the email from the school saying the investigation into her complaint was “completed” and that she could review it before the school came to a decision on the case. That email, from Bucci, also noted that Axley’s case had been moved over to the Office of Community Life, which handles Liberty Way infractions.

And it was when Axley went to review the report that she discovered that the photographs she had submitted as evidence had been removed from her file without her knowledge.

Axley was dumbstruck and resubmitted the photos. “At that point, it honestly felt like they were trying to sabotage my case,” she said.

Soon after Axley resubmitted her photo evidence, she received another email from the school. It said the committee reviewing her case — which Axley recalled was composed mostly of men — had reached a decision: By a “preponderance of the evidence,” her alleged assailant was found “not responsible” for rape.

In its accompanying explanation of the decision, the committee focused on the account of one student who recalled that Axley was on top of the man she said assaulted her, and that the man had told Axley to get off.

But that student, who requested anonymity, told me that the Title IX office misrepresented her testimony. Liberty quoted her saying it was “obvious” that Axley was trying to initiate sexual contact, but she said she doesn’t recall saying that.

Prior to our conversation, the witness had not seen the decision letter in which she was quoted. She was shocked that her name was used in the letter, despite her repeated requests to the Title IX investigator that she remain anonymous. “They made me sound like a casual, coldhearted individual with this statement,” she said. “I was very scared and very traumatized from this situation and it affects my life even today.”

Neither Aaron Sparkman, the university official who signed Axley’s decision letter, nor Bucci, who interviewed the two witnesses, responded to requests for comment.

The letter also did not detail the recollections of Logan Pratt, the friend of Axley’s who was so concerned about the man being overly physical that he texted Axley the morning of the incident to see if she was OK.

Instead, Liberty referenced Pratt’s observation that Axley was drunk.

“The way they wrote it down makes it seem that I went to the Title IX office not to help her but to get her in trouble,” said Pratt, who was shocked when I showed him the letter. “This reads very backwards to me. It is honestly scary that they twisted my testimony like this. It makes me wonder how many other people’s words they tweaked the way they did to my testimony.”

Pratt said that he went to the Title IX office of his own volition because he was “concerned for Lizzie’s safety” after what he saw at the party. But when he was interviewed, he said, he thought “they didn’t seem to care much about Lizzie,” and instead he felt like he was “interrogated for what I had been doing at the party.”

He said, “It all felt so backwards and strange, like they were trying to find me guilty by association.”

Pratt, who entered Liberty in the fall of 2017 on a full scholarship, said that five months after reporting Axley’s case, he was expelled from the school for violations of the Liberty Way, including drinking and partying.

“It sounds like the university was crafting their own narrative that had less to do with finding the respondent responsible or not, but rather with framing the complainant as someone who was ‘not worthy,’” said S. Daniel Carter, who helped author the Clery Act that covers how schools should handle and disclose sexual assaults.

Liberty’s letter with its decision on the investigation also did not mention the other evidence submitted by Axley — not the text messages from friends that weekend expressing concern about what had taken place, and not the photographs of her bruises and cuts.

Experts who reviewed the facts of Axley’s case and the committee’s subsequent letter explaining its decision were shocked that the Title IX office seemed to have removed evidence from Axley’s file and were confused as to why the decision made no mention of it.

“That’s outrageous,” said Rebecca Leitman Veidlinger, an attorney who specializes in Title IX. “The complainant herself offered the photos. There are ways to safeguard evidence of a sensitive nature. But to disregard key evidence? I can’t imagine the justification.”

After Axley learned that Liberty had dismissed her complaint, she thought there was still a chance the school might reconsider. “Yesterday my rapist was found not guilty. I would like to appeal this decision,” she wrote in a May 2018 email to the university.

Less than two weeks later, the appeal committee reaffirmed it had found the man not responsible for the alleged rape.

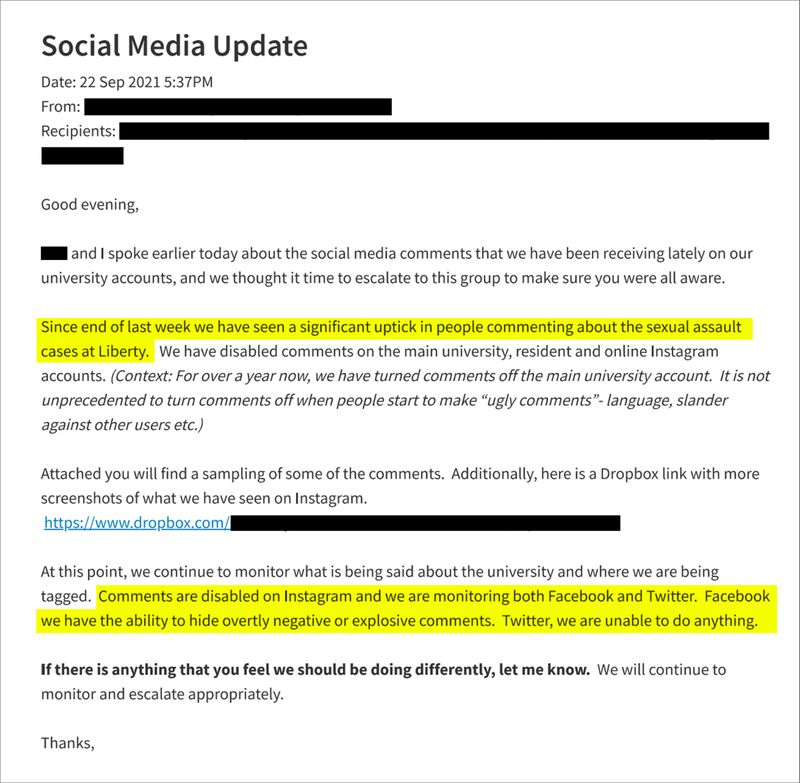

This past summer, Liberty University’s handling of sexual assault came under closer scrutiny. The lawsuit filed in July by 12 women was followed by an outpouring of concern, frustration and calls for action on social media. A petition demanding that Liberty change how it handles sexual assaults gained hundreds of signatures in a few days.

Scott Lamb, then Liberty’s communications chief, watched it all with increasing concern, but with little surprise. He had been warning top Liberty leadership about the growing wave of concern and frustration.

“There seems to be the notion that there are many (not few) skeletons in LU’s closet when it comes to ‘mishandling sexual assault allegations,’” Lamb wrote to top Liberty leadership in a May 7 email. “Culturally, this seems to be a pattern: 1 person makes an accusation about Bill Cosby/Harvey Weinstein/Matt Lauer etc…. And overnight there are a dozen people who say the same thing. True, LU is not Bill Cosby…But I’m talking about the Court of Public Opinion. And I fear that we are about to enter into a season of being found guilty in that court.”

Lamb said his email received no response.

As summer slipped into fall and Lamb watched tensions on campus and beyond deepen, he encouraged university higher-ups to at least acknowledge the problem.

Instead, he said Liberty decided to do what it could to silence the criticism.

A Sept. 22 email from the school’s marketing department to top Liberty officials, including the school’s president, briefed them on the “uptick” in “people commenting about the sexual assault cases at Liberty” on the school’s various social media platforms. “We have disabled comments on the main university, resident and online Instagram accounts,” the marketing executive wrote.

“Comments are disabled on Instagram and we are monitoring both Facebook and Twitter. Facebook we have the ability to hide overly negative or explosive comments. Twitter, we are unable to do anything,” the executive wrote. “If there is anything that you feel we should be doing differently, let me know,” the email concluded in bold.

The scramble over how to respond continued. Liberty’s Jerry Prevo, who replaced Jerry Falwell Jr. as president last year, planned to give a speech early this month directly addressing the concerns, and in particular the lawsuit filed by the dozen women.

“I have asked a law firm to look into the facts on all these cases,” said a draft of Prevo’s speech. “Nothing is going to be swept under the rug.”

“If our policies and procedures should be changed, I’ll change ’em,” Prevo’s proposed speech continued. “Not just because Title IX, but because we need [to honor] God in all we do at Liberty and we need to do so standing on Biblical truth. That’s The Liberty Way.”

Lamb saw the proposed language and immediately wrote to his colleagues that it “will make things far worse.” Lamb pointed out, for example, that the law firm the school brought in hadn’t been hired to investigate the allegations. It was hired to defend the school against the suit.

One of the lawyers was on the email chain and agreed with Lamb’s concerns. “We’re here to represent the University in a lawsuit,” she wrote. “It’s an important distinction.”

The speech was canceled.

Instead, president Prevo briefly discussed the issue at a school prayer meeting. “We want you to feel safe,” Prevo said. “We don’t want any sexual harassment or sexual abuse.”

Lamb said he was fired less than a week later.

“The problem isn’t the PR; the problem is the problem,” said Lamb. “And until Liberty addresses the problem — first by telling the people who got hurt here that they are seen and heard — the healing can’t begin.”